Ride-Share vs. Reality:

Built on Sand – The Data Gap Behind Bermuda’s Ride-Share Pilot by BTOA

When governments propose sweeping changes to essential services like transport, the public expects those decisions to be built on evidence. Policy should flow from data, not from anecdotes. Yet Bermuda’s Ride-Share Pilot Programme, which authorizes 150 new permits for private vehicles, has been introduced without any visible foundation of evidence.

This is not an abstract criticism. In 2018, The Royal Gazette reported that the Transport Control Department (TCD) stopped monitoring taxi operating hours in 2010 after a “policy decision.” That meant one of the most basic performance measures — how many taxis are on the road and for how long — has gone unrecorded for more than a decade. A year later, the paper confirmed the same point: taxi laws exist, but they have simply not been enforced.

Layer onto that the fact that dispatch companies, which are required by law to submit reports of jobs, cancellations, and operational statistics, have not done so since at least 2014. In 2024, when Shadow Minister Susan Jackson requested those reports in Parliament, Transport Minister Wayne Furbert produced only three months of partial data from a single company. Nothing else was available.

So when the government now claims that introducing 150 ride-share vehicles is a data-driven response to shortages, the question must be asked: what data?

What the Ride-Share Pilot Is?

The pilot, introduced in 2023, was pitched as a solution to Bermuda’s “number one complaint” from visitors — difficulty finding transport late at night or during peak demand. The scheme allows private vehicles to operate as part-time taxis during the high season from April to September, and on weekends and public holidays during the off-season.

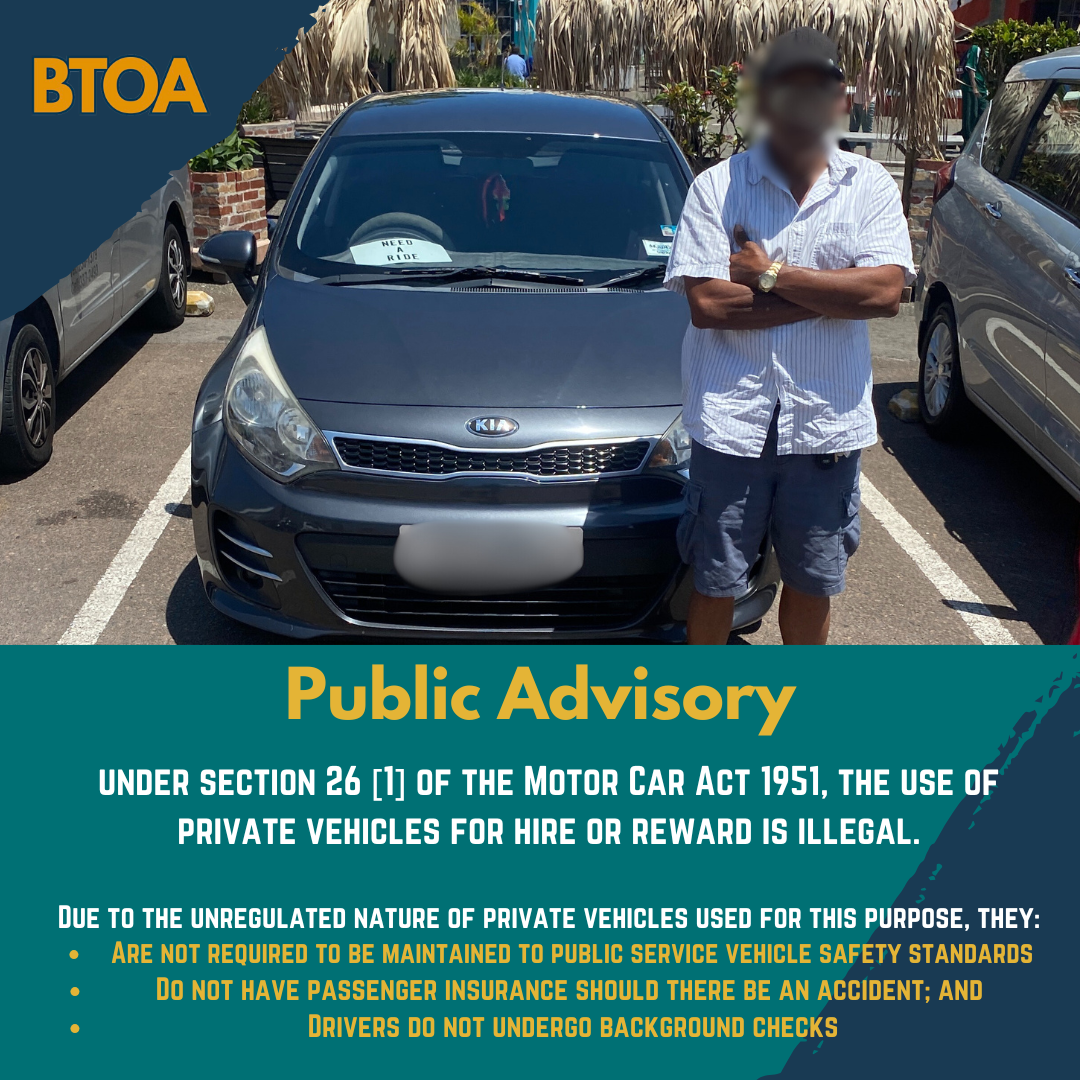

Each permit is reported to cost $1,000, and operators are barred from street hails. They must accept jobs only through one of Bermuda’s four licensed dispatch companies. Insurance requirements were initially left vague, though the government later suggested appropriate coverage would be arranged with local insurers.

On paper, the pilot looks like a neat fix. But when placed against the backdrop of missing data and unenforced reporting laws, it is revealed as a policy built not on evidence but on expediency.

Missing Data: A System Gone Dark

The Motor Car Act 1951 and the Taxi Dispatching Service Regulations 1987 require dispatch companies to register with TCD, equip their fleets with GPS and mobile data terminals (MDTs), and submit operational information. The Public Service Vehicle Licensing Board (PSVLB) is required to furnish annual reports to the Minister, who must lay them before the Legislature.

In practice, none of this has happened.

- TCD admitted in 2018 it had not monitored taxi hours since 2010.

- Dispatch reporting has not been enforced since at least 2014.

- No PSVLB annual reports have been made public in recent years.

For over a decade, the system has operated in the dark.

Anecdotes as Policy

Instead of evidence, policy has been shaped by frustration. Visitors complain about long waits, residents post about no-shows on social media, and hotel managers lobby for more vehicles. These experiences are real, but they are not statistics.

No one disputes that Bermuda’s transport service has been uneven. Some drivers refuse short rides or avoid less profitable destinations. But without data, there is no way to measure how widespread those problems are, or whether they justify adding 150 new vehicles.

The result is policy driven by perception rather than proof — a dangerous precedent.

International Comparison

Globally, ride-share initiatives have only been launched after rigorous data collection and impact studies. In London, Transport for London publishes quarterly datasets on private-hire and taxi operations. In Toronto, the city studied taxi wait times, ride demand, and fare economics before licensing Uber. In New York, the Taxi and Limousine Commission collects detailed trip data for every yellow cab and ride-share vehicle, publishing monthly reports.

By contrast, Bermuda is attempting to graft a ride-share model onto a system that has not collected even the most basic taxi data in more than a decade.

Why This Matters

Transport is not simply about convenience. It is about safety, fairness, and economic stability. When the government admits it has no data, when dispatch companies fail to report, and when regulators do not enforce, adding more vehicles is not a solution. It risks destabilizing the industry further and undermining public trust.

Conclusion

Bermuda deserves a transport system built on solid ground. Right now, ride-share is being built on sand — a programme introduced without data, justified by anecdotes, and layered onto a regulatory framework that has not been enforced in years.

Before a permit is issued, the government must show the evidence. If the data exists, publish it. If it does not, explain why policy is being made in the dark.

Because the real question is not whether Bermuda needs more vehicles. It is whether Bermuda can afford more decisions made without proof.