Ride-Share vs. Reality:

Who Regulates? by BTOA

In our first article, we showed that Bermuda’s ride-share pilot was built on no data. Now we ask a second question: who is responsible for regulating and enforcing this system, and can they be trusted to do so?

The Transport Control Department (TCD), the Public Service Vehicle Licensing Board (PSVLB), and the Minister of Transport are supposed to safeguard standards, enforce laws, and protect the public. But their record tells a different story: one of retreat from enforcement, abandoned monitoring, and silence on complaints.

The Regulators and Their Mandates

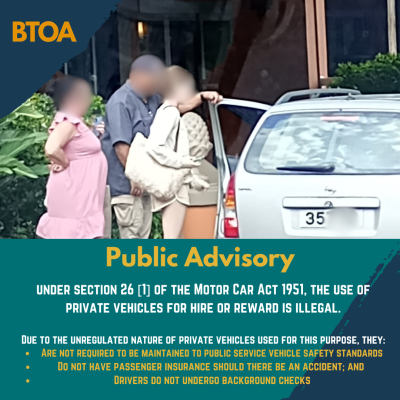

The Motor Car Act 1951 gives TCD authority over licensing, inspections, and compliance. The PSVLB regulates permit issuance, investigates complaints, and can suspend or revoke licences. The Minister of Transport directs both, setting policy and introducing legislation.

Together, this framework should ensure accountability. Instead, it has enabled neglect.

Abandoned Enforcement

The clearest evidence of failure came in 2018, when The Royal Gazette reported that TCD had not monitored taxi operating hours since 2010, due to a “policy decision.” That meant no official record existed of whether taxis were meeting their 16-hour daily requirement.

At the same time, dispatch companies — legally required to file reports — have not submitted them since at least 2014. In 2024, Shadow Minister Susan Jackson requested those records. The Minister could only produce a partial three-month report from a single company. Nothing more was available.

This is not oversight; it is abandonment.

Complaints Without Transparency

The PSVLB is legally obligated to furnish annual reports to the Minister, who must lay them before Parliament. Those reports should include complaint statistics and enforcement outcomes. Yet in practice, no such reports have been published in recent memory. Passengers are left doubting whether their complaints matter, and operators are left in the dark about industry standards.

The Ride-Share Enforcement Challenge

Against this backdrop, the ride-share pilot sets new rules: operators must hold a PSV licence, work only through dispatch apps, and carry insurance. On paper, it looks orderly.

But in reality, the same institutions that abandoned enforcement for taxis are now being asked to oversee a more complex, tech-driven system. If TCD has not enforced operating hours for 14 years, why would the public trust it to enforce ride-sharing? If dispatch companies have not filed reports in a decade, why would they suddenly comply now?

Risks of Weak Oversight

The risks are not hypothetical. Without enforcement, passenger safety is at risk, as unvetted or under-insured operators slip through. Market fairness is undermined when taxi owners bear heavy regulatory burdens while ride-share operators face lighter oversight. And public trust is eroded when complaints vanish into silence.

International Lessons

Cities that have embraced ride-sharing did so with strong regulatory frameworks. London publishes quarterly private-hire compliance reports. New York requires detailed trip-level data from every Uber, Lyft, and yellow cab. Toronto mandated economic studies before introducing new licences.

Bermuda, by contrast, has allowed its regulators to go dormant — and is now piling ride-share onto that foundation.

Conclusion

Ride-share is being layered onto an enforcement vacuum. Laws exist, but they have not been enforced. Reports are required, but they have not been collected. Complaints should be published, but they have not been shared.

Until Bermuda can show it has rebuilt enforcement, ride-sharing is not modernization. It is deregulation in disguise.

The question remains: who regulates Bermuda’s transport system — and can the public trust them to regulate ride-share when they have admitted they are not regulating taxis?